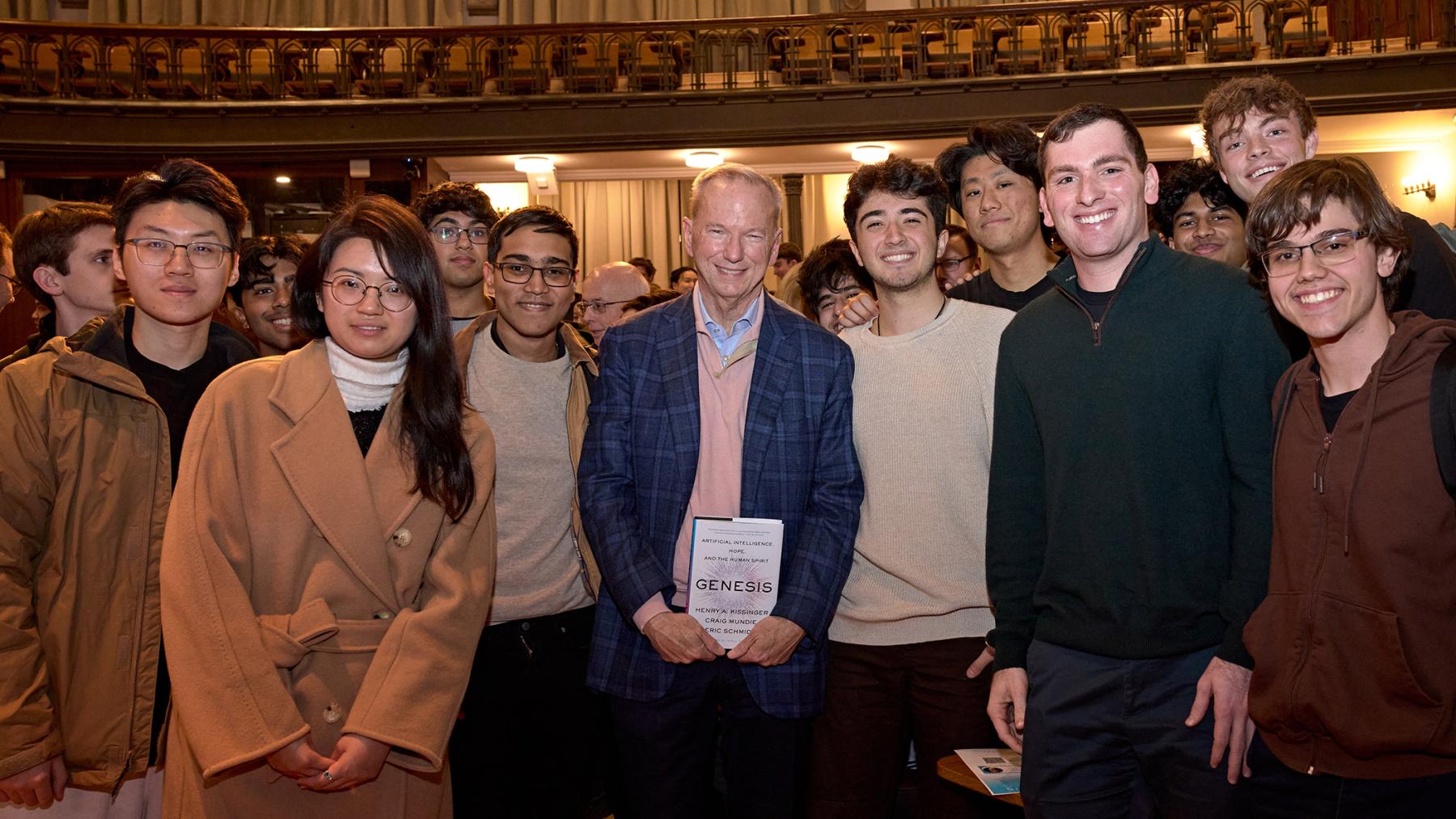

Eric Schmidt ’76 returned to campus on Nov. 20 to discuss his new book, “Genesis: Artificial Intelligence, Hope, and the Human Spirit,” with Provost Jen Rexford ’91. Photos by Steven Freeman

Former Google chairman and CEO Eric Schmidt ’76, whose Princeton education prepared him to help guide the information technology revolution, urged Princeton undergraduates and graduate students from a wide range of academic disciplines to tackle the “inconceivably large” opportunities and challenges that artificial intelligence (AI) now presents.

Schmidt, a prominent technologist, entrepreneur and philanthropist, called the potential economic and societal impact of AI bigger than the information technology revolution. He spoke at Princeton in conversation with Provost Jen Rexford ’91, the Gordon Y.S. Wu Professor in Engineering, and in a subsequent audience Q&A.

“Figure out a way to get yourself into the middle of these curves that go like this,” Schmidt said, swooping his hand toward the sky. “I’ve been most successful, thanks to Princeton, that I was at the beginning of each of these revolutions. That’s where you want to be, because when they grow, it’s unbelievable. Chemistry, science, math — all of them are going to be transformed by this. In that sense, you’re the best generation to take it on. It’s your turn now.”

The special event on Wednesday night, Nov. 20, in McCosh 50, which was livestreamed on the University’s YouTube channel, took place one day after Schmidt published his new book, “Genesis: Artificial Intelligence, Hope, and the Human Spirit,” co-authored by the late Henry Kissinger and Craig Mundie. The book outlines strategies for navigating the age of AI and equips decisionmakers to seize the opportunities without falling prey to AI’s darker forces. Tickets quickly sold out, with students and other members of the Princeton community snapping up enough tickets to fill the historic lecture hall within hours of its announcement. The first 250 attendees received a free copy of the book.

President Christopher L. Eisgruber ’83 introduced and welcomed Schmidt: “The book was published just yesterday, but already, reviewers are hailing it as a profound exploration of the ways that AI will test our understanding of what it means to be human and raise new questions about knowledge, power and the possibilities for human progress.”

Rexford began the conversation by asking Schmidt about his undergraduate studies in the early 1970s. Although Princeton did not have a computer science department until 1985, Schmidt carved out his own academic path by taking every computer-related class the engineering school offered. He also interned at nearby Bell Labs where he worked with Stu Feldman ’68 on the Unix operating system. (Feldman attended Wednesday’s lecture and currently serves as president and chief scientist at Schmidt Sciences, a philanthropic organization that accelerates scientific knowledge and breakthroughs.)

“By the time I graduated from undergraduate at Princeton, I had a graduate level of understanding of computer science,” Schmidt said. “That’s when the luck starts. When you get at the origin of something that’s going to explode, don’t quit — ride it.”

Schmidt went on to do graduate work at the University of California, Berkeley, and then began his career with computer technology pioneers, including Xerox’s Palo Alto Research Center. As Google CEO and chairman from 2001 to 2011, Schmidt oversaw the company’s transformation from a small Silicon Valley startup to a global tech giant, alongside founders Sergey Brin and Larry Page.

Rexford, who served as chair of Princeton’s computer science department for eight years before becoming provost in 2023, was well versed on the themes of “Genesis,” and her own expertise helped drive the conversation. “One of the things I really loved in the book,” Rexford said, “was the discussion of polymaths, the importance they play in making major leaps forward, and the idea of AI being a polymath in your pocket.”

Today’s AI systems, “are now testing at 80 or 90% of the graduate level knowledge in every field. Now there’s nobody, not even the brilliant people here, who can do all of that in every field,” Schmidt said. “The next thing that happens is the agentic revolution, which is essentially the development of agents that use these things to solve problems. That polymath will be available to each and every one of you, and every citizen in United States, and, in fact, every citizen of the world. That is a very big deal.”

Rexford noted Princeton’s motto, “In the Nation’s Service and the Service of Humanity,” and asked Schmidt where he saw the greatest opportunities for AI to help. Schmidt described the potential of machine learning and large language model technology in improving healthcare, education, public safety and quality of life issues.

“Let's talk about the positives: You should expect an enormous sort of a Cambrian explosion of medical solutions to problems that have bedeviled us,” he said, highlighting AI’s promise in drug discovery and precision medicine. “The systems that we’re building are very good at multi-scale prediction problems, and the reason is because large language models, roughly speaking, predict the next word. There’s not much difference between predicting the next word and predicting the next part of a protein sequence. Algorithmically, they’re very similar.”

On climate change, “new energy systems require new materials, fission, fusion, new transmission and so on,” Schmidt said. “That’s going to be AI-developed.”

In global education, “the single best thing you can do for the world is get it more educated,” he said. “Why do we not have an AI system that just educates everyone in their own language, in the way that they learn? Strikes me as a learnable proposition.”

At the same time, Schmidt said, AI also worries him. “When I’m in Silicon Valley, it feels like it’s everything, everywhere, all at once,” he said. “So many people in your generation who are trying new ideas. I can assure you, the humans in the rest of the world … are not ready. Their governments are not ready. The doctrines are not ready. They’re not ready for the arrival of this.”

“I really think this University should embrace these ideas and questions, because I don’t know the answers,” Schmidt said. “My standard answer is the graduate students will figure this out: Write a Ph.D. on the 20 or 30 questions that are in this book and at least you’ll do something new. This is the arrival of a new intelligence that rivals human intelligence and is a very big deal for ethics, for society, for child rearing, for economics.”

When microphones were made available to members of the audience, Schmidt leaned forward in his chair, engaging students who had questions, and responded with candor on wide-ranging topics from social media to national defense.

A Ph.D. student in history asked how AI can enhance research in the humanities, and Schmidt suggested seeking out someone who is building a language model around historical research. He also recommended Google’s new NotebookLM tool, an AI-powered research assistant that scholars can use to get “deeper insights” out of their own writing, notes and sources.

A junior in computer science wondered about the potential of incorporating machine vision and other non-language inputs into AI, and Schmidt encouraged her to pursue a Ph.D. “I think your idea about integrating sensor models and vision models is a new one,” he said. “You should do that. And at Princeton, as an undergraduate, you can do it.”

A fourth-year graduate candidate in molecular biology lamented the deleterious effects of social media on the current political landscape. “One of the things that’s worth saying is that none of us thought when we invented social media that we would become a threat to democracy,” Schmidt said. “With Henry [Kissinger], I would make these statements about optimism and so forth, and he said, ‘The only problem with you, Eric, is that everything you’re saying is inconsistent with any historical record.’ … This time around, the reason we wrote the book was to get everybody to start thinking about these questions.”

For Schmidt, hearing from the students and engaging with their new ideas and research connected him back to his own Princeton story. “For each of you, that origin story is really important,” he said. “Don’t give up that opportunity. They don’t come along very often, and they occur when you’re very young.”

“It is a privilege to be here,” he said at the end. “I knew it the day I came in, and I still feel it today. Thank you very much.”